Mike Portelly

The serious introduction to underwater film making came a few months later, The same producer Jon put me in touch with a friend of his shooting a large project for Pepsi cola for the US.

I had to go for an interview in Kingly Court in Soho. There were three big established modelmaking companies there already. I had to wait for Bob Hinks from Asylum Models to finish and met the guys from Eagle models and then Bowtells who were also up for the job. I felt out of my league.

I was both flattered and annoyed that they were seeing these people and I was resigned to not getting the gig.

My turn came and I briefly met Mark the producer and then I was introduced to Mike.

Mike was a small man, but larger than life, he was an excited, and enthusiastic character, who had to be centre of attention and holding court. I thought he was a little crazy, but I instantly liked him and wanted him to like me!

Mike Portelly had had a successful career as a dentist and taken up scuba diving.

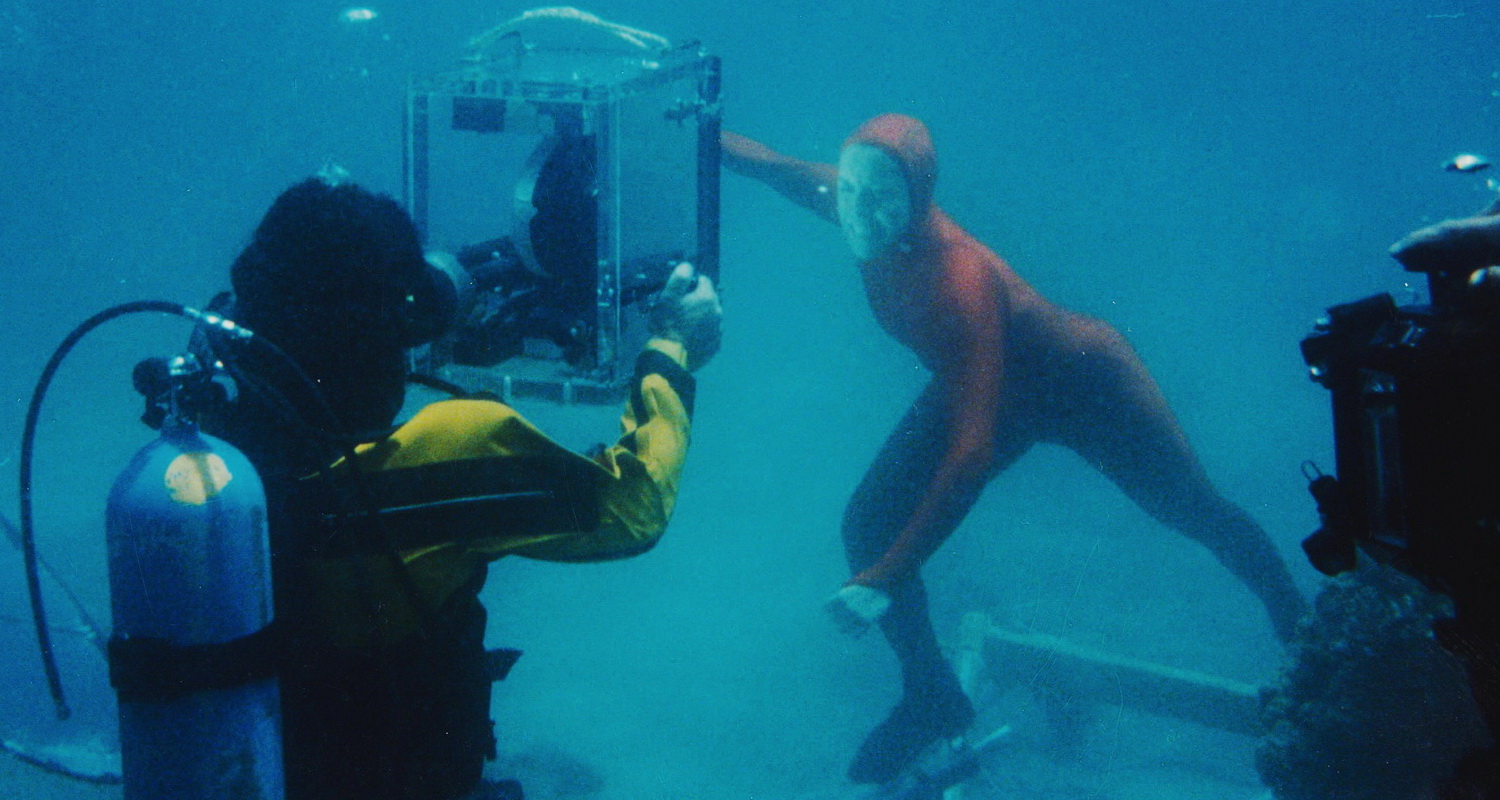

On a trip to Sinai he dived with a wildlife photographer David Pilosof. he was hooked and bought himself a camera and a housing and took off. within a year he had won all the underwater wildlife prizes and moved on to photographing his girlfriend underwater, selling a feature to the Sunday times mag. He then met and commissioned Peter Scoones to make him a housing for a Bolex and with his friends he made a film.

“The Oceans Daughter” Mikes movie won prizes at Montreaux and every underwater film festival in the world and introduced Mike to his hero, Cousteau and gave him credibility in the world of film.

He was picked up for a couple of smaller commercials, Jon Nigel had worked on Mikes movie and done one of his spots and he had mentioned me to Mike.

He talked me through his ideas and showed me clips of his films and they were brilliant, like nothing else I had seen or done, he had a knack of being interested in me and how I could help him. Peter Scoones came into the office and was pleased to see me. It helped and we got on, next thing Mike was driving me back to my studio in Blackfriars. Mike had a new flashy lotus that was probably the fastest ash tray I have been in, Mike smoked constantly, and the car was full of fags and chocolate. Later I started to work it all out, I wanted the job and I had to make it work but knew that in the time i could not do it all. Eventually the key Props were made at my studio and Asylum Models made masses of scaled up ice cubes. The ice cubes had to look real in closeup to match Pepsi beauty shots, but they had to work underwater. each cube was a 40cm cube and it was difficult to cast clear resin in that quantity without it discolouring or cracking. They had to have a space that could be filled with air or water to be adjustable for neutral buoyancy! I made giant acrylic lemon slices with the same properties.

I had a 4000sq ft floor in the warehouse, it was a large bohemian art studio. I lived in the back in a fantastic loft like space. I employed my friends and it was a good atmosphere to work in. Mike enjoyed coming over despite the smells and dust from the fibreglass. I made 4ft diameter lemon slices and smaller ones with the same buoyancy properties as the ice.

Everything was packed up and shipped off to the location.

The shoot was to be based in Eilat Israel and we would work from a dive boat, “The Sue Ellen”, 2 guys from my studio came out with me and my learning started…

The core of Mikes crew became lifelong friends we would work together for years.

We had a real mix of people on the boat including Mikes brother John a just qualified GP who was our Medic! Joining Peter Scoones in the Camera Dept was a very young Mark Silk working as a loader.

This was one of only 2 shoots Mike had a topside dp Steve Smith with Wick Finch as his gaffer.A few years later on we did a Job for Thompson Freestyle and Pete Bijou lit it. Mike preferred to do his own lighting assisted later by Mark Silk.

Working on Mikes shoots was unlike any other, everyday away could have been a shoot day he didn’t do down, rest, or prep days. We were in the water before first light and out at sunset.

Light, water temp and visibility were key to the style of Mikes jobs so most shooting is within 10 meters depth, and we only surfaced for air and lunch.

Despite Mikes medical background ,health and safety wasn’t really on Mikes list, he was as single minded as any other director in search of a shot.

Mike always had experienced divers around and eventually had a tight crew… mooring a boat could be extremely complicated.

You have to keep the boat out of the light and the frame and still close enough to work from, without swinging around.

Although we worked near the surface, inevitably someone had to walk an anchor along the seabed or tie it around a coral head.

And be ready to free it at any time, if Mike wanted to chase a gap in the clouds.

This and keeping track of everyone was quite a serious task on its own, but if you were in the water you would be expected to hold a reflector, dress the set, build a rig, shepherd fish, or check mikes air, because he never did.

For this we had Robin, Shmulik and Bobby, they spent the day keeping us safe and doing everything that needed to be done!

Unless we were filming actors or models in the water, then they were the key crew to plan buddy systems and protect their charges from the dangers of the underwater environment and an even more dangerous director.

Filming in the red sea particularly, as often amongst the spectacular corals were stone fish, scorpion fish, urchins or fire coral.

Filming with girls, kids and babies, Mike would always feel they could do a bit longer underwater than they should, so it was important the safety divers took charge.

I took a lot of scaffold fittings with me and the first job was to build a drop rig for the props. and camera hoist.

A 35mm camera in a housing is a very heavy beast and a major job to get in and out the boat.

The safety divers became key in the rigging department and we had some amazing rigs to build. Mike liked to work at shallow depths but he liked to shoot against the cobalt blue of deep water.

We would build a tubular frame like a room 4m to 6m wide and hang the frame on lift bags, this gave us an adjustable depth work space that presented its own problems.

We would typically be 35 to 40 m above the seabed and would anchor our rig to a coral head or point.

This worked for a while but as we worked and the rig expanded it would need adjusting.

Divers forgot about the physics that held the rig in place and would hang reflectors tools or spare air tanks on to the rig. So all the time the lift bags were filled with more air to even the load. The anchor line could become dangerously tort and had to be very secure.

A complicated shot could involve an actor 2 buddy divers a camera man and assistant sparks on reflectors and some art dept or a bubble rig. It was not unusual to have 8 or 9 divers in the water and if one of them is weary and hangs on the rig ears popped till someone noticed the whole set was sinking.

Robin Middleton, Me, and Mark Silk

Bob Johnson Robin and me with 2 of the boat crew in Bimini

Dan Travers Being led into set Halls Mentholyptus Ad Eilat

Below, Mike and I planning a shot

Robin Scoones and Mark Silk Egypt